Misinformation vs. Disinformation in Politics

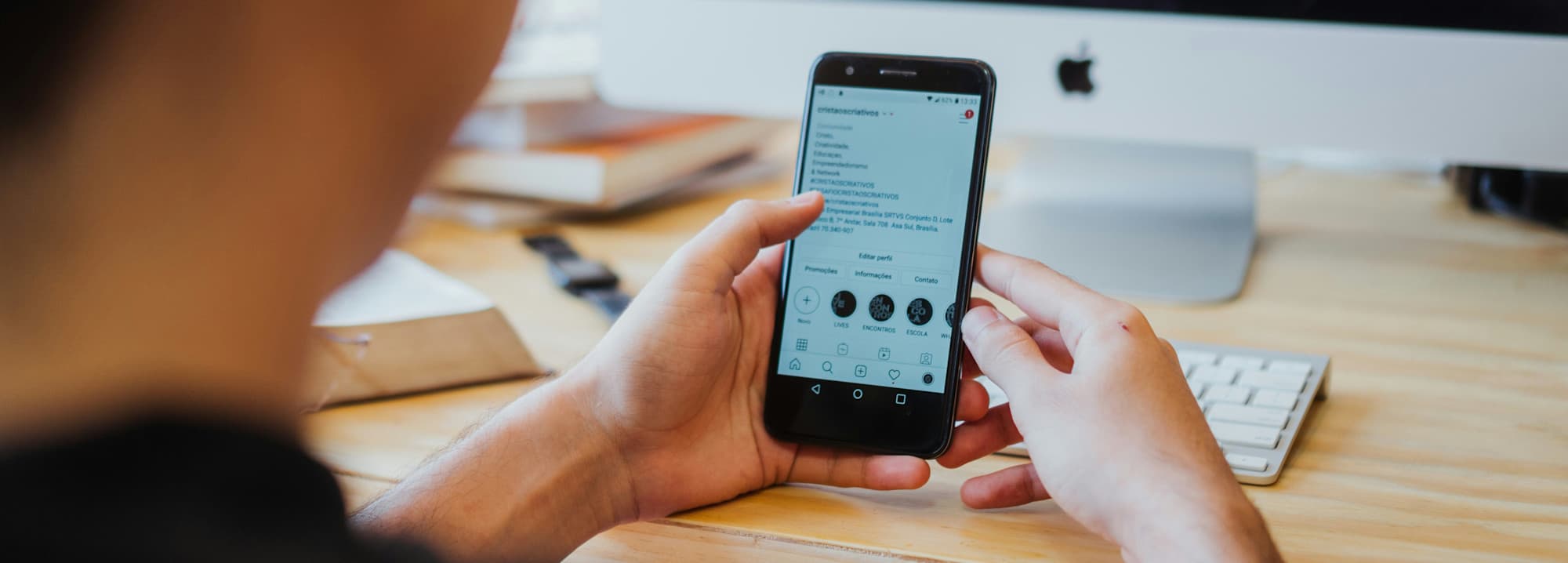

The digital age has made information more accessible than ever. With just a few swipes, we can scroll headlines, watch political commentary, and share stories with friends and family. Social media has democratized communication, but it has also made it easier for false information to spread at lightning speed.

When it comes to our democracy, the facts matter. But in a world overflowing with information, distinguishing between truth and falsehood isn’t always easy. That’s where the difference between misinformation vs. disinformation becomes critical.

Why the Distinction Matters: Misinformation vs. Disinformation

Both misinformation and disinformation describe false or misleading information, but the intention behind them is what sets them apart.

Misinformation: False information spread without intent to deceive.

Disinformation: False information spread deliberately to mislead.

Understanding the distinction matters because while both can harm democratic institutions, disinformation is particularly dangerous. It is the weaponization of mistrust for political or personal gain.

A 2025 survey found that 60% of Americans over the age of 65 reported seeing information they believed to be false or misleading every day. NewsGuard research reports that 49% of Americans say they’ve fallen for at least one false news claim. In 2016, Pew Research reported that Americans were already deeply concerned about fake news and misleading details in the media. Nearly a decade later, the stakes have only grown higher as falsehoods shape perceptions of everything from local elections to global health crises.

What Is Misinformation?

Misinformation is unintentional falsehood. It spreads when people share something inaccurate because they believe it’s true.

For example, imagine a rumor during an election claiming a candidate plans to raise taxes on the middle class, even if no such proposal exists. A supporter might share that rumor out of genuine concern, not realizing it’s false. Unfortunately, the effect is the same: the rumour persists, voters are misled, and public trust is eroded.

To make things more complicated, factual mainstream news articles are frequently shared alongside misinformation narratives, giving credence to the misleading claims and boosting their reach.

Even without malicious intent, misinformation:

Misleads voters about critical issues.

Fuels unnecessary polarization.

Weakens trust in institutions and leaders.

Today, news outlets and social media platforms are working harder to catch misinformation early. Independent fact-checkers review questionable posts, flag inaccuracies, and alert users. But misinformation doesn’t just live online. It spreads in community conversations, family chats, and word-of-mouth discussions.

What Is Disinformation?

While those who share misinformation don’t mean to be deceptive, disinformation is deliberate deception. Disinformation is shared intentionally to manipulate, mislead, or harm.

Political campaigns, foreign actors, and bad-faith influencers often use disinformation to:

Undermine opponents.

Stir division among voters.

Suppress turnout among targeted groups.

One recent instigator of disinformation is the Russian propaganda group Storm-1516. During the 2024 presidential election, Storm-1516 created false claims about Kamala Harris’s involvement in a hit-and-run and spread fake rumors about sexual assault allegations against Tim Walz.

Unlike misinformation, which may be corrected through education, disinformation is harder to combat because it is intentional. It’s part of a strategy, not an accident.

Who Is Targeted by Disinformation?

Disinformation campaigns are rarely random. They are designed to exploit vulnerabilities, divide communities, and weaken trust.

Some of the most common targets of disinformation campaigns include:

Political Opponents: Candidates are frequent targets of disinformation during election season. False claims about their personal lives, exaggerated policy positions, or doctored videos can spread quickly online, like the Storm-1516 stories about Harris and Walz. Third-party and Independent candidates are especially vulnerable to disinformation campaigns since they lack the backing and protection of a major party.

Marginalized Communities: Disinformation often targets groups who already face systemic discrimination. By spreading false stories about immigrants, racial minorities, or women in politics, campaigns sow division and discourage civic participation. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, disinformation falsely claimed certain racial groups were more resistant to the virus, discouraging vaccinations in vulnerable communities.

Everyday Voters: False narratives are used to confuse or discourage citizens from voting. This can take the form of misleading information about voter ID laws, polling locations, or election dates. Before the 2024 election, viral falsehoods about non-citizen voting and manipulated vote counts circulated widely, eroding public confidence in election integrity and keeping many from the polls.

Institutions and Media: Disinformation also targets trust in democratic institutions themselves, like courts, journalists, and election administrators. If citizens believe these institutions are corrupt or illegitimate, it becomes harder for democracy to function. For instance, the Russian “Doppelganger” campaign created fake versions of mainstream media outlets like Fox News and The Washington Post to spread pro-Russia propaganda, blurring the line between credible journalism and manipulation.

By deliberately targeting these groups, disinformation polarizes communities, makes constructive debate harder, and suppresses participation, especially among marginalized groups. Disinformation also delegitimizes institutions, weakening the foundations of and faith in democracy.

This targeting is exactly why disinformation is more dangerous than misinformation.

LEARN MORE: Explore how media literacy can help combat misinformation and disinformation.

Misinformation and Disinformation in the Digital Age

False information is not a new challenge. Long before smartphones and social media, societies grappled with both misinformation and disinformation.

Even in ancient Greece and Rome, political leaders spread rumors about rivals, sometimes unknowingly, but often strategically. Once the printing press was invented, the battle for factual information began. Newspapers in the 1800s were notorious for sensationalism, and hoaxes like the 1835 “Great Moon Hoax” show how misinformation could take off when fact-checking lagged behind.

In the 20th century, state propaganda machines like Nazi Germany’s Ministry of Propaganda and Soviet ‘active measures’ campaigns like Operation Denver showed how disinformation could be weaponized on a global scale

However, the rise of the internet blurred the line between misinformation and disinformation and made the spread of both even more difficult to contain:

Mistakes, hoaxes, and rumors spread faster than corrections.

State actors and coordinated campaigns exploit digital platforms to deliberately mislead at scale.

AI-generated content and deepfakes make it even harder to know what’s real.

Social media’s algorithms reward engagement, and few things spread faster than sensational or emotionally charged claims.

False stories can go viral in minutes, shaping perceptions before corrections can catch up. Platforms now rely on third-party fact-checkers and automated tools to flag misleading content, but enforcement is inconsistent, and disinformation campaigns often adapt faster than responses.

LEARN MORE: See how AI is shaping politics and how we can use it to strengthen democracy.

Combating Misinformation and Disinformation

Research from Tufts University looked at polarization, education levels, age demographics, news viewership rates, and trust in digital news to determine what areas of the United States are most vulnerable to misinformation and disinformation. Tellingly, a majority of the most vulnerable states have historically been battlegrounds during presidential elections.

Misinformation tends to cluster in politically competitive, ideologically divided states with aging and less educated voters.

So what can be done to help the most susceptible members of our communities and promote truth and transparency? We need solutions at both the systemic and personal levels.

At the systemic level, our institutions and society must:

Strengthen independent fact-checking and media literacy education.

Hold leaders accountable when they knowingly spread falsehoods.

Support reforms that prioritize transparency and fairness in political communication.

At the individual level, we all need to:

Check for credibility before sharing information. Who is the author? What’s the source? Why is it being shared?

Seek diverse perspectives. Don’t rely on a single outlet or algorithm and challenge your own echo chambers.

Discuss news constructively. Share what you learn in respectful conversations with neighbors, friends, and community members.

In a 2025 Pew survey, 70% of Americans reported saying the spread of false information online is a major threat to our nation. By practicing these habits together and urging our institutions and social media platforms to do and be better, we can slow the spread of misinformation and build resilience against disinformation campaigns.

A Local Solution to False Information: Listening Beyond the Loudest Voices

The fight against misinformation vs. disinformation isn’t just about fact-checking headlines. It’s about protecting democracy itself. Both forms of false information erode trust, divide communities, and distort elections.

While misinformation and disinformation are often seen on a national scale, they are also felt at the local level. Too often, elected officials mistake the loudest voices online or in town hall meetings for the views of their whole constituency. This creates space for misinformation to distort priorities.

A better approach is running representative surveys. Broad constituent surveys can capture what the entire community actually thinks, not just what’s trending in comment sections. When leaders listen broadly and ground decisions in facts, they govern more effectively and help rebuild public trust.

At GoodParty.org, we believe strengthening democracy means giving leaders the tools to stay connected to the people they serve, not to partisan narratives or viral falsehoods. If you’re in office, join the waiting list today to get the tools you need to listen to your community.

By learning the difference between disinformation vs. misinformation, strengthening fact-based decision-making, and supporting Independent leaders who prioritize people over parties, we can build a stronger, more resilient democracy.

Photo by Creative Christians on Unsplash

Want to be part of the solution? Join GoodParty.org’s community of Independent thinkers to connect with nonpartisan candidates, volunteers, and elected officials looking to get beyond the noise of misinformation online.